Intro to Database Systems : Concurrency Control - Scheduling problems

In real life, users access a database concurrently.

Database access is done through transactions. What is a transaction?

- a unit of work that has to be treated as “a whole”

- it has to happen in full or not at all

A real life example of a transaction is money transfer:

- first, withdraw an amount X from account A

- second, deposit to account B

The previous operation has to succeed in full. You can not stop halfway. Database transactions work the same way. They ensure that, no matter what happens, manipulated data is treated atomically (you can never see “half a change”).

Atomicity is part of the ACID properties that a DBMS has to maintain:

- Atomicity: either all actions from a transaction happen, or none happen

- Consistency: the database starts from a consistent state and ends in a consistent state

- Isolation: execution of one transaction is isolated from other transactions

- Durability : if a transaction commits, its effects persist in the database

Now what can go wrong?

- If not scheduled properly, concurrent process may alter the isolation and consistency properties.

Let’s imagine a problem where 2 users reserve a seat for a flight:

- customer 1 finds a seat empty

- customer 2 finds the same seat empty

- customer 1 reserves the seat

- customer 2 reserves the seat

Customer 1 will not be happy. This introduces the notion of serializability. There needs to be a concurrency control mechanism through a schedule.

A sequence of transactions executed chronologically is called a schedule. It is a representation of how a set of transactions are executed over time. It can contain the following actions:

- read R(X)

- write W(X)

- commit (after completing all its actions, all the operations should be done and recorded)

- abort (after executing some actions, if we abort, none of the operations should be done/recorded)

A commit or an abort is mandatory in order to have a complete schedule.

A serial schedule is a schedule without interleavings: all operations are executed consecutively.

Conflicting operations are present in a schedule when those operations satisfy the following conditions:

- they have to belong to different transactions

- they have to access the same data object X

- at least one of the operations is a W(X) (write on X)

Let’s see a couple of conflicting operations:

- The Write-Read Conflict : reading uncommitted data

- The Read-Write Conflict : rereading data that has been altered since the first read.

- The Write-Write Conflict : losing updates

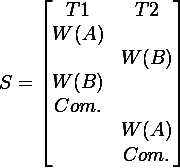

The Write-Read Conflict, also called reading uncommitted data or dirty-read occurs when a transaction T2 tries to read a database object A, modified by a transaction T1 which hasn’t been committed. When T1 continues with its transaction, data of object A is inconsistent. The next picture helps illustrating the scenario:

In other words, a dirty read is when a transaction is allowed to read data from a row that has been modified by another running transaction and that modification has not yet been committed.

The Read-Write Conflict, also called unrepeatable reads, occurs when a transaction T1 has to read twice a database object A. After the first read, transaction T1 waits for transaction T2 to finish. T2 overwrites object A and when T1 reads A again, there are 2 different versions of A. T1 will be forced to abort: it is the unrepeatable read.

A real life example of this situation is when Bob and Alice are on Ticketmaster and they want to book tickets for a show. There is only one ticket left : Alice signs-in, finds that the ticket is expensive and takes the time to think about it… Bob signs-in and buys the ticket instantly and then logs off. Alice decides to buy the ticket and finds out that there are no tickets left.

The Write-Write Conflict, also called overwriting uncommitted data, occurs when there are lost updates. The attempt to make this scenario serial will always give two different results: either transaction T1’s version or transaction T2’s version.

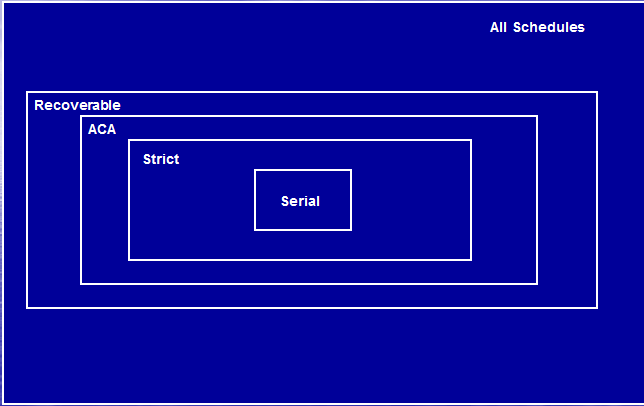

Once some concurrent transactions applied on a database, a schedule is serializable if the resulting database state is equivalent (equal) to the outcome of the same transactions, but executed sequentially, without overlapping in time. This is what we aim for. A schedule that is serializable can also be :

- ACA : avoid cascading abort

- recoverable

- strict schedule

The best way to verify if a schedule is serializable is through a dependency graph.

To build a dependency graph we can follow this procedure:

- 1) Represent every transaction by a node

- 2) Is there a transaction Ty that reads an item after a different transaction Tx writes it? If yes, draw an edge from node Tx to node Ty.

- 3) Is there a transaction Ty that writes an item after a different transaction Tx reads it? If yes, draw an edge from node Tx to node Ty.

- 4) Is there a transaction Ty that writes an item after a different transaction Tx has written that item? If yes, draw an edge from node Tx to node Ty.

Don’t forget to remove the edge that you just drew if you are actually aborting your transaction.

In order to have a serializable schedule, the dependency graph has to be acyclic (it doesn’t have any cycles, closed paths).

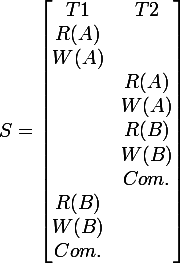

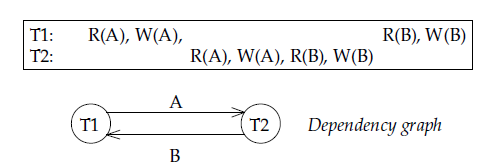

The following schedule is not serializable:

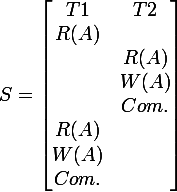

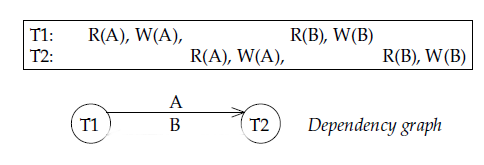

The following schedule is serializable:

Now how to know when a schedule is strict?

- when an object written by a transaction T cannot be read or written again until this transaction T commits or aborts.

How to know when a schedule is avoiding cascading aborts?

- when an operation can only read data that has been committed

How to know when a schedule is recoverable?

- when for each transaction where Ty reads some data written by Tx, the COMMIT operation of Tx appears before the COMMIT operation of Ty.

The point of enumerating all those schedule classes is to define some concurrency control : measures such that non-serializable execution can never happen.